If land were religion, the Green Belt would be its high priest. Revered. Untouchable. Endlessly invoked in speeches and consultations as the last bulwark between concrete and countryside. Say the phrase “Green Belt release” in a public meeting and you can watch elected members age visibly before your eyes.

But beneath the reverence lies a policy creaking at the joints, weighed down by decades of confused thinking, public misunderstanding, and political timidity. The question is no longer whether the Green Belt needs review — it’s whether we’re capable of admitting it.

What Was the Green Belt For?

The Green Belt wasn’t designed to be a beauty contest or a landscape designation. It wasn’t about protecting England’s green and pleasant land in general. It was a policy tool with clear strategic aims, introduced after the Second World War to:

- Prevent urban sprawl

- Protect the setting of towns and cities

- Avoid the merging of neighbouring settlements

- Encourage urban regeneration by containing development within existing areas

It was, in theory, a bold and rational spatial device — a ring of restraint around major urban areas, shaping growth inward rather than outward.

It wasn’t a promise that every green field would be protected. Nor was it based on ecological value, biodiversity, or landscape character. Yet over time, these misconceptions have grown roots of their own.

Is It Still Doing That?

In some places, yes. But in many others, the Green Belt is now doing something else entirely — and not always for the better.

Rather than stopping sprawl, it often pushes it further out. Development leapfrogs the belt, landing in towns and villages beyond it. The result? Long commutes, car dependency, and splintered communities. Meanwhile, the inner edges of cities — close to jobs, services, and public transport — remain frozen, even where land is of low landscape or ecological value.

The idea of “urban containment” works best when there’s a strong policy to build up, not just out. But the pressure on land and the scarcity of brownfield sites in many areas mean that containment has turned into constraint. And constraint, without direction, creates sprawl by stealth.

It’s also worth saying — quietly, because this tends to ruin dinner parties — that not all Green Belt land is lovely. Much of it is unremarkable: intensively farmed, inaccessible, ecologically poor. You can’t walk through it, picnic in it, or enjoy it from a train window. It is “green” in planning terms only — and sometimes not even that.

Why Don’t We Reform or Remove It?

Because, quite simply, it is politically radioactive.

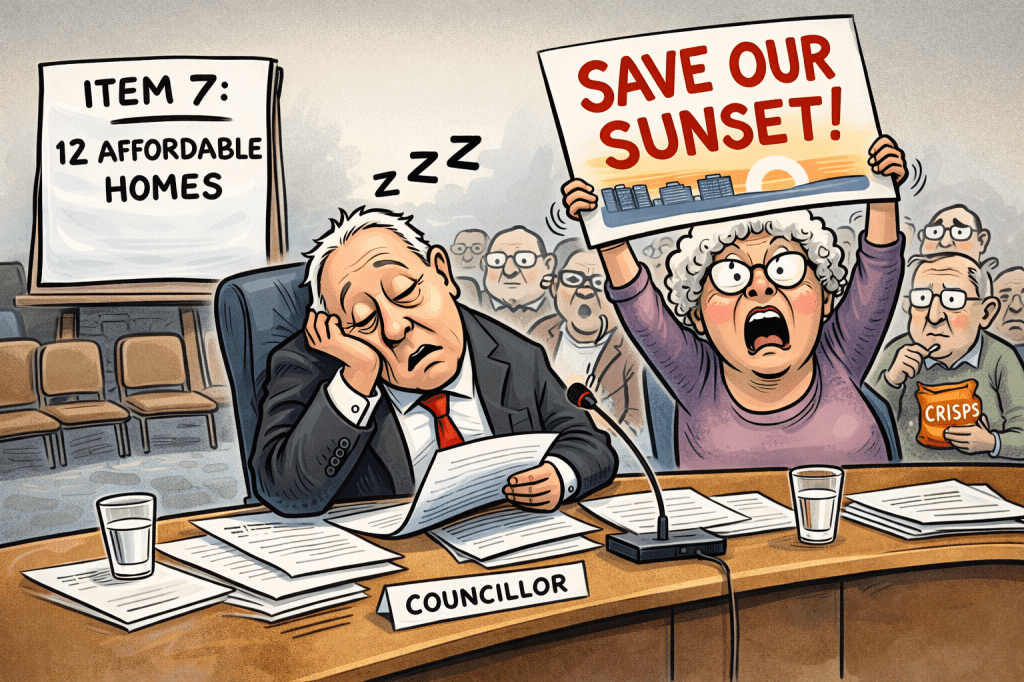

Any attempt to review or redefine the Green Belt is met with howls of betrayal. National politicians know this, and local politicians feel it — in their inboxes, on doorsteps, at public meetings. Defending the Green Belt is electorally safe. Challenging it is not.

Never mind that many people conflate Green Belt with “all green fields.” Or that they assume it’s about beauty, when it’s about boundaries. These myths are now baked into the public consciousness — and they’re not easily undone in a planning policy footnote.

The result? Endless tinkering. “Exceptional circumstances” here. Strategic swaps there. Quiet incursions through local plans, but no national reckoning. We’re rearranging the deckchairs while pretending the ship is unsinkable.

The Problem With Tweaks

The idea of treating the Green Belt as permanent — as something beyond review — is oddly unplanning-like. Everything else in planning is negotiable. Everything else can be tested, balanced, consulted on. But the Green Belt is often treated as dogma, not policy.

And when we do tweak it, we do so under immense pressure. Sites are carved out through bruising local plan examinations or court battles. The burden of proof is heavy, the politics even heavier. So instead of a rational, national conversation about growth, we end up with a patchwork of exceptions — each one fought for like a planning war of attrition.

Meanwhile, homes are still needed. Infrastructure still ages. And policy limps on.

What Might a Rational Policy Look Like?

Start with a clean sheet. Ask: where should growth go, based on need, sustainability, connectivity, and environmental value?

Some areas of Green Belt might still be essential — for setting, separation, or containment. But others, frankly, are candidates for review. And not because we want to pave paradise. Because we want to build homes in places that make sense.

We should be protecting landscape, nature, and accessibility — not lines drawn in 1955 on the basis of how far a city had spread post-war. We should stop pretending that all Green Belt is sacred, and instead start treating it like the policy tool it was meant to be: strategic, revisable, and responsive.

Conclusion: The Sacred Cow Needs a Vet

The Green Belt served its time. It brought discipline to post-war growth. It helped shape cities and protect countryside. But we are now using it to fight a very different battle — against a housing crisis, against climate goals, against economic inequality.

And in that battle, the Green Belt is not always on the right side.

Yet despite the urgency, too often the loudest voices in the room belong not to planners, nor to those affected by housing need, but to local chapters of the CPRE — well-meaning, undoubtedly passionate, but often unqualified and unaccountable. Many worship at the altar of the Green Belt with a fervour that borders on the devotional. Their objections are predictable, relentless, and almost always against change.

The question is: should we really allow such groups, however earnest, to shape national planning outcomes? Is it right that housing delivery, urban sustainability, and spatial policy should be hostage to those who view any development as a threat, and who see Green Belt as sacred ground, not strategic tool?

It’s not heresy to ask. It’s just planning.

Let’s stop treating the Green Belt like a relic beyond question. Because if we can’t even ask whether this tool is still fit for purpose, we’ve already given up on planning as a profession — and on homes as a right, not a privilege.