New housing is timid. Not understated. Not elegant. Just timid.

We talk endlessly about respecting “local character” as if it were some sacred text — one we must interpret carefully and never deviate from. But more often than not, “character” is just shorthand for “don’t frighten the neighbours.”

The result? Entire estates that could have been built anywhere. Three-bed boxes in compliant red brick. Token gables. Faux chimneys. Heritage by spreadsheet.

And all in the name of “context”.

We’ve mistaken repetition for reverence. Somewhere along the way, “contextual” became a synonym for “copy-paste.”

What Do We Even Mean by ‘Character’?

Let’s be honest — nobody really knows.

Is it style? Materials? Roof pitch? Is it the curve of the road, or the fact that there’s no pavement on one side? Is it the view of the church spire from a layby near the recycling bins?

Ask ten planners and you’ll get ten definitions. Ask a committee and you’ll get a leaflet quote.

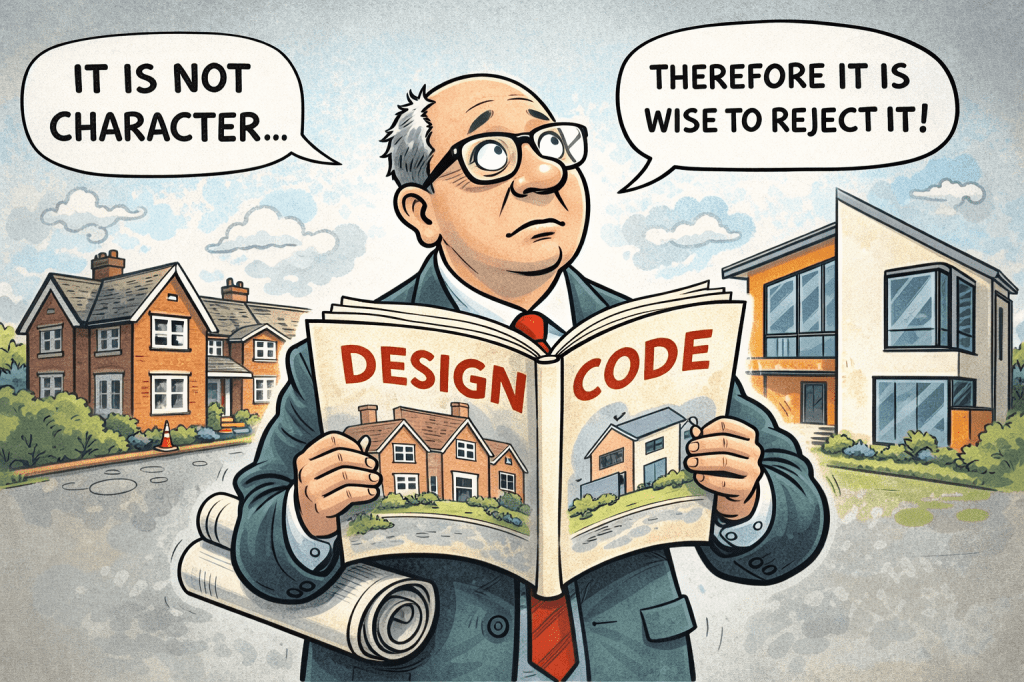

“Character” has become a convenient umbrella for objectors, officers and councillors alike. It’s used to oppose the unfamiliar, resist the modern, and excuse the dull. Sometimes all three.

We throw it around like it’s quantifiable. But what we’re really doing is policing anything that dares to stand out.

The Real Consequence: Timid Design

Developers, understandably, play it safe. Why risk bold design if it means delay, committee, and a possible refusal? Why go near “contemporary” when it only takes one councillor to call it “out of keeping”?

So we end up with endless applications that blend into a beige sea of inoffensiveness. Streets designed not for place-making, but for avoidance. Avoidance of controversy, of risk, of anything that might require explanation.

Planners don’t help. Too many design comments focus on whether something “respects the grain” or “reflects the prevailing vernacular.” Too few ask whether it’s any good.

The result is housing that looks like it was assembled from a nationwide kit — the same porches, the same window proportions, the same brick-effect panels.

It’s not protecting local identity. It’s manufacturing national monotony.

And let’s be clear — we’re not preserving history here. We’re preserving mediocrity. We’re holding up 1930s suburbia like it’s some kind of design benchmark, when half of it was built without a shred of architectural ambition.

A Word on Design Codes

Design codes aren’t the villain. When used well, they raise standards, give clarity, and stop the worst excesses.

But when followed rigidly — or written to pander — they stifle imagination. They produce developments that tick boxes, avoid objections, and utterly fail to excite.

We’ve created a planning culture where the path of least resistance is always the path of least quality.

If a developer wants to try something genuinely different, they don’t look to the code for guidance — they brace for battle.

This is how we end up with places that have no connection to geography, climate, history, or anything human. Just the hollow reassurance that it looks like the last one that got through planning.

When Did We Become So Afraid of Boldness?

That’s the question planners, designers and councillors should be asking themselves.

When did bold design become so threatening?

When did we decide that anything striking was “out of character”?

When did place-making give way to appeasement?

Not everything needs to be iconic. But we ought to expect something that reflects the time it was built in. A willingness to speak the language of today, not whisper through the voice of the past.

Because if we only ever build to imitate, what will future generations look back on and say: yes — that was ours?

There’s a danger in overstatement, yes. But there’s just as much danger in perpetual understatement. We’re raising entire communities without architectural identity, then wondering why they feel disconnected and unloved.

Closing Thoughts

This obsession with character — this fear of straying from it — has robbed us of architectural courage.

I was a partner in an architectural firm for 5 years. In that time I moved from safe design principles to a far bolder approach. My success rate amongst LPA’s dropped from around 90% to nearer 60% in those 5 years.

But bold design is not about erasing the past. It’s about building the present. A present that’s confident, specific, and unapologetically of its time.

Let’s be clear-eyed: most new housing doesn’t “respect local character.” It mimics a softened version of a version of a version. It’s a photocopy of familiarity.

And it’s dull.

Respecting context doesn’t mean copying it. It means engaging with it — responding to it — and sometimes challenging it.

Because if we never take a risk, we’ll never build anything worth remembering.